wild thing

i make my heart sing

This is the most disgusting piece you’ll read all day.

It was recently published in daisy cashin’s (hardly loathsome) Substack, I hate these people. daisy enjoys a kind of hardboiled innocence; a Southerner whose direct, open prose resists the irony of the mean streets of NYC, even if the skuzz reveals itself in every close observation. It’s damn fine writing that gives me hope. Doesn’t get better than this.

Also: I’m hosting a zoom on Lily King’s Heart the Lover: 10/26 at 8pm. I’m hoping it’ll be like your favorite English seminar, except nobody’s in charge. Be in touch if you’d like to join us.

Now, for some ick. xx

Anybody who grows up around ghosts knows it’s not just the dead doing the haunting.

At home sometimes, I’d feel my skin crackle and my stomach sink, and I’d know the mood was turning. I’d rush out the screen door quick enough that the metal couldn’t bite my heel. Outside in the swampy woods, the creepy stuff was visible and made its own kind of sense.

Out back were wetlands, a sedge meadow, and a young birch forest whose limits I never reached, respecting the neighbors’ rusty, barbed wire. I collected frog eggs in old frying pans to safeguard their hatching; dug leaves out of the stream so the Atlantic wouldn’t dry out; marveled at the cruelty of nature.

I still replay the horror of watching an orange newt I’d caught, swarmed and devoured by ants. I think of the broken blue egg and the tiny, wet bird, crushed by our tomcat, Sylvester. I loved him and he disgusted me, driving his needly teeth into that shell, arcing his back as he gulped and swallowed the baby robin—still living, but not yet born. The nature videos I watched at friends’ houses confirmed the comfort of my ambivalence: I was rooting for the hunted zebras. Or was I? The lion cub was hungry, too. Nature had its balance. Wildness was savage, but its through-line was straight and clear and therefore, innocent.

I knew where I stood in the woods. I was as wild as the robin and the tomcat, which meant I must be pure, too. Inside, I worried I wasn’t. Was I to blame for the shadowy moods that turned my skin to gooseflesh? Maybe I’d disrupted Barefoot Charlie, who died upstairs in 1825 with much unfinished business. Maybe I wasn’t enough to satisfy my father, who sat hunched over the kitchen table, missing Mom who’d gone to work again. There was moralizing inside the house—that first touchpoint of civilization—and I didn’t know the codes. But in the woods, I was unburdened.

At twenty-four, I found myself in a concrete cul-de-sac in Houston. I’d followed a boy— the man who’s now my husband—but I fet adrift. I enjoyed his work parties (though always wrongly dressed) and learned to make friends with the ladies who lunched. But in the evenings, I’d wander from park to park, searching for some part of my spirit that had been splintered off and left behind. Sitting on a bench outside the Rothko chapel, my eyes flying over the first pages of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, I understood what I was missing: the innocence of the creepiest wild things.

Dillard writes about walking around a pond, searching for frogs. She finds one and braces for its hop, but instead, she watches it collapse, its innards sucked out by a water bug.

Soon, part of his skin, formless as a pricked balloon, lay in floating folds like bright scum on top of the water: it was a monstrous and terrifying thing. I gaped bewildered, appalled. An oval shadow hung in the water behind the drained frog; then the shadow glided away. The frog skin bag started to sink.1

This was what I’d been searching for: a wild place where I could wander and remember that nature’s cruelty was neither bad nor good. Without the woods, I’d lost touch with my instinct; that feral edge that defied blame.

Dillard again, on the beauty of that gutted frog:

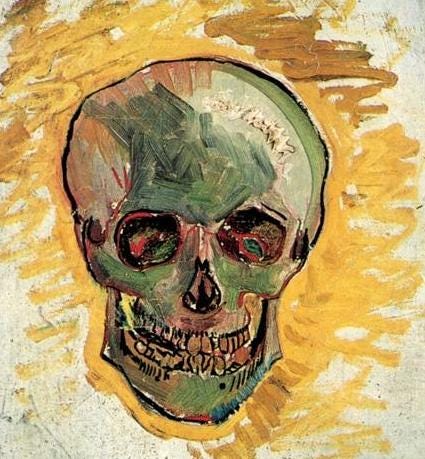

Cruelty is a mystery, and the waste of pain. But if we describe a world to compass these things, a world that is a long, brute game, then we bump against another mystery: the inrush of power and light, the canary that sings on the skull.2

I am that canary. I learned it, driven out of the house to the swampy woods. I lost her for a while; clipped her wings to learn the codes. Now I understand that the game is holding your instinct while playing—just enough—at the rules of civility.

We live by fields now, not forests. If I want our boys to get lost, I have to walk them a half mile down the dirt road to the mouth of the trees. I encourage them to go alone, but they never do. We hike together on weekends and I wish I weren’t with them—I want them alone, free of the specter of adult. I’ve been socialized, after all. My gaze always implies it. I want them free of all that.

I tell myself it’s good they have nothing to escape. What a gift, to be happiest at home; to run from no ghosts. Still, I worry about what they’re missing. Bruce, the toddler, is the only one who wants to get lost all day in the overgrowth at the edge of our yard.

He’s most attracted to the neglected corner by the back fence, where the ferns are so tall, their leaves arc into tunnels. A few months ago, I followed him, circling a path of hidden stones. I stood a few feet behind as he paused, bending over a slab of dark, sparkling granite. He squatted with his back flat—flexible in ways I cannot fathom—and grabbed a gray pebble between his thumb and forefinger.

I smiled, pleased by his dexterity. These are fine-motor milestones, gestures that mean his body’s forming as it should. His learning’s innate, instinctual. “Good boy!” I chirped as he squeezed the little pearl. I bent down and realized it was a grub: a roly-poly that had balled itself against his predatory fingers.

“Give it to me,” I said, hard and fast, suddenly understanding his plan. “Give me the bug.”

I lashed out to grab it, but the larval creature was already in his mouth. I stuck my thumb between Bruce’s slick cheek and the ridges of his teeth, but I couldn’t shove my fingers further—his bites, I’ve learned, draw blood. I slid my hand out and watched him swallow.

He turned and toddled on and I followed, stomach-sinking, ashamed. I imagined him feverish and vomiting. How would I explain it to the doctor?

But I knew he wouldn’t get sick. It was only a grub. After a while, I smiled at my own hypocrisies—these aftershocks of guilt and control; the useless vestiges of a civility I’m unwinding. When has wildness ever been convenient? When has it not been kind of fucking gross?

And who am I to clip the wings of savagery and innocence?

Dillard Annie, A Pilgrim At Tinker Creek, (Harper Magazine Press, 1974), 5.

Ibid, 6.

“In the woods we return to reason and to faith “ Emerson

This essay leaves me dumbfounded in its beauty. Thank you, Isabel, for sharing it here. xo